Voices from the sea are heard at dawn.

Cries for help break the darkness and tell the stories of our time.

So does the silence from 3,600 people who have drowned so far this year in the Mediterranean Sea.

As autumn turned into winter this year, the words about the refugee crisis have lost their urgency.

We’re making another attempt.

We’re writing this story straight from the water.

THE COAST OF

THE DEAD

Reporters: Erik Wiman, Kenan Habul and Carina Bergfeldt

Photo: Andreas Bardell and Peter Wixtröm

Translator: Katie Dodd Syk

For four weeks this fall, Aftonbladet has been on the Greek island of Samos. We have followed the Swedish Sea Rescue Society and participated in rescue operations of the Gula Båtarna (The Yellow Boats) campaign.

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2015:

After a few days of calm weather, the wind has increased and is approaching gale force. In the narrow sound between Turkey and Samos, the waves quickly become high and steep. But they don’t stop the refugee boats from coming.

The bad weather is not noticed in the bays where the smugglers launch their overcrowded rubber boats. But out in the open water, the boats become toys at the whim of the sea and are often pushed against the life-threatening cliffs of Samos.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2015:

“LIFE IS SPITTING IN MY FACE”

It is the salt water that makes her blind.

The sea attacks with full force and every new wave that pounds her cheeks makes it impossible to see. Her only defense is to squint and blink. Her knuckles are white from tightly grasping her children in the boat.

It is the 8th of November, 2015, and tomorrow she will no longer be alive. She is sure of this.

Fear paralyzes her. Not even during the nights of bombing can she remember being this frightened. The explosions came one after the next, and were often followed by silence for several hours. The sea, however, seems to be everywhere at once.

“The boat is very safe,” a man had said when she hesitated to climb aboard. She can’t even count how many other lies she heard there on the beach. “New motor, and just one hour’s journey by boat, absolutely no danger…”

Now, six hours later, everything has been revealed. Even the sea has lied, where it lay calm and flat before. The first waves were almost a surprise. The children on board had even laughed when they first got wet, for the water was not cold. Not then at least.

Now all 37 bodies on board are shaking.

They had been picked up by a car in Izmir and driven one and one-half hours to a stoney beach. The men were masked, stressed, and irritated. They gathered all the belongings and threw them down into the bottom of the boat.

The first time the motor failed, they’d gone just 10 meters out on the water. The masked men made a few adjustments and they were on their way again. It took seven tries before they even got out to the open sea.

Why hadn’t they canceled the whole thing?

In the chaos of her thoughts, she is able to hold onto a single one:

“Life is spitting in my face as a farewell, life is spitting in my face…”

She’d been able to turn away from the wind when she huddled over, but the fear that she would see her children torn away from her was too strong.

The engine wheezes like an old man and then cuts out again. For the umpteenth time – she does not know – but it now seems to have died for good. There are no more screams of fear. Everyone is silent, except for those who are vomiting.

It has been one year since the family left Aleppo. They fled after the oldest son was almost killed by a bomb. He was playing football in the street when the attack came, and afterwards said that the blood from his friends was not red, but rather brown after the dust cloud settled.

The family fled to Turkey that same afternoon. It took one year of work for her husband to save enough money to continue their flight.

$1000 per person – and now, they’re all going to die.

She offers a prayer:

“Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raaji’uun.” We belong to God and will return to him.

The boat is half-filled with water. The luggage that is packed with their life is completely soaked. She feels that her daughter shaking and looks down at her dark hair and pink earmuffs.

“I love you,” she says.

Greece looks so near, from the other side.

The mother’s name is Mardula and she survived the journey across the sea. On November 8, the wind blew between 12 and 15 meters per second on the water between Turkey and Samos.

After having driven for four hours, the boat finally rammed against the cliffs of the Greek island.

All of the 37 people aboard, including eight children and one pregnant woman in her 8th month, managed to climb up on a rock.

Without help, they would never have been able to escape.

Since the first alarm, the Swedish Sea Rescue Society has saved over 690 people in distress along the Samos coastline. Many of them would not have survived without this help.

THE COAST OF THE DEAD SAMOS, GREECE

DROWNING ACCIDENTS IN THE STRAIGHT:

At least 200 people in 2015

AVERAGE WAVE HEIGHT:

1.5 meters

NUMBER OF REFUGEES:

500 – 1000 per day

DISTANCE TO TURKEY:

2-12 kilometers

SMUGGLER’S RUBBER BOATS

CONSTRUCTION: Inflatable boats. Worn motors of 25-30 hp.

4-7 meters long.

PRICE FOR ONE SPOT ON BOARD:

$1000

TOURIST FERRY FROM KUSADASI TO SAMOS

CAPACITY

150 persons

PRICE FOR A TICKET:

€24

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 4, 2015:

“NOW I ONLY LIVE FOR HIS SAKE”

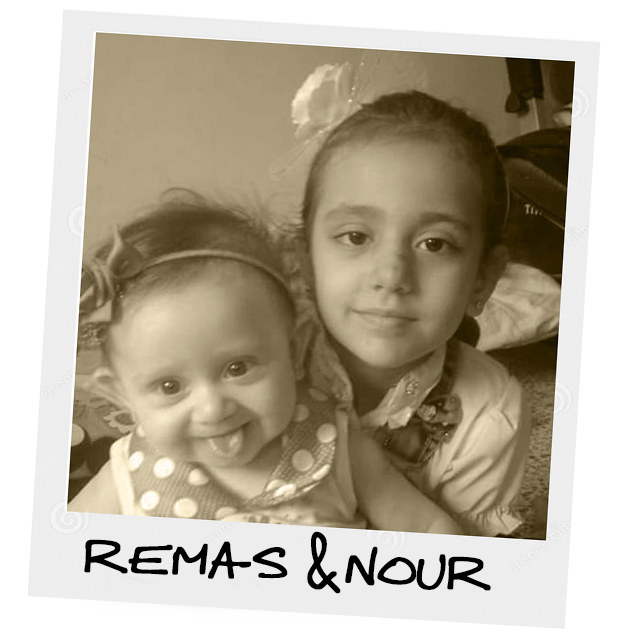

Three-year-old Mohamed believes that his mother and two sisters are in Germany.

He does not know that they drowned outside of Samos.

Now he only has his father left.

Every night, the pictures come back.

Maher Fanosh shouts to them to come out. He wants to go in and save them, but he must take care of his son, Mohamed. He asks a man to hold him, but the man says no. “I cannot swim.”

A few hours later, when it is day, Maher Fanosh identifies his wife and daughters from the mobile pictures that a Greek diver has taken when they recovered the bodies.

The boat sunk 25 meters from the shore of Samos on the night of Sunday, November 1; 11 women and children died.

Every time Mohamed sees a baby being fed with a bottle, he asks about Remas. When he gets candy, his father lays a portion to the side. He says that it is for his sisters, who are waiting for them together with their mother in Germany at the home of Mohamed’s uncle.

One time, Mohamed saw his father cry.

“I lied and said that I had met a father who had lost his children,” answered Maher Fanosh.

When they started to take in water, the Turkish smugglers said that it was normal. He didn’t let the men bring the women and children up from below deck. “It’s not necessary to scare them,” he said.

The smugglers disappeared without a trace just when the accident occurred.

“I would kill him if I saw him again,” says Maher.

His wife and daughter were buried in the middle of November at a Muslim graveyard on the island of Kos. In a hotel room in Athens, Maher waits to hear if he can travel to Germany, to his brother’s family. There is no one left in Syria. His siblings are spread out all over Europe and the Middle East. One brother was kidnapped by IS.

In the beginning of October when he decided to flee with his family, Maher Fanosh had never heard of Samos or Kos.

“Sometimes I think that if they had died in Syria, at least I could have buried them in our own country.”

When Mohamed peed himself one night, Maher didn’t really know what to do – his wife usually took care of these things. Every day, he takes his son to a playground 20 minutes from the hotel. The walk clears his head; he hopes he’ll get tired enough to sleep for a few hours.

Mohamed smiles when he drives in the toy car, he chokes with laughter when his father swings him high. In these moments, even his father’s sullen face lights up a little bit.

“Now I only live for his sake,” says Maher Fanosh.

As you read this, a new family is preparing themselves for the journey over the Mediterranean Sea. Tonight, yet another mother will hold her child close to her in a water-filled boat.

So far in December, as Europe prepares for Christmas, 97 people have died in the Mediterranean Sea.

Every silhouette symbolizes a dead or missing refugee from the Mediterranean this year.

3,671 at the time this was written.

At least 1,200 of them were children.